The complicated history of the women's suffrage movement

August 3, 2020

On August 18, 2020, our nation celebrates the 100-year anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment. This accomplishment proved an arduous journey, but women across the United States victoriously secured their right to vote after decades of effort.

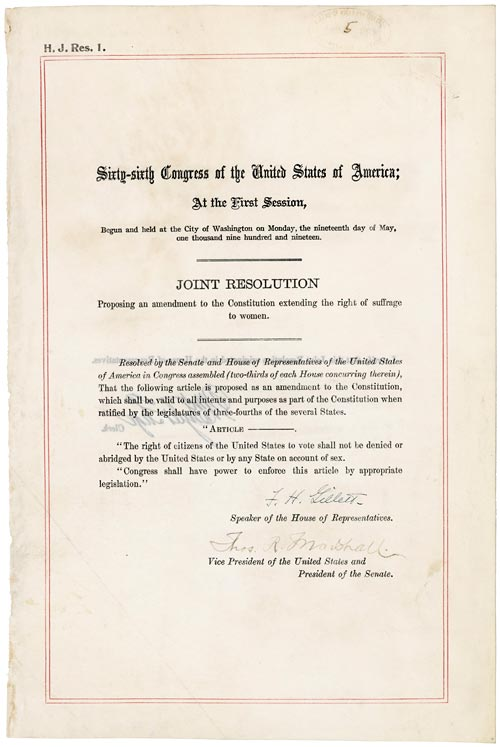

19th Amendment to the United States Constitution, 1920.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The 19th Amendment was first introduced to Congress in 1878 and, while suffragists tirelessly advocated for the right to vote, most states were not in support of the amendment until 1912. Slowly, women's fearless efforts gained legitimacy and, in 1918, President Woodrow Wilson changed his position and supported the suffrage movement.

Women’s suffrage has a more complicated history than many are likely aware of. This blog serves to highlight the countless challenges overcome by Black suffragists to attain the same voting rights as white men and women.

Black women and the vote

“...with us as colored women, this struggle becomes two-fold, first, because we are women, and second, because we are colored women.” - Mary B. Talbert, Crisis (1915)

The Headquarters for Colored Women Voters in Chicago, 1916. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

Women’s rights and the antislavery movement shared momentum and partnerships prior to the Civil War. Both formerly enslaved and freed Black women joined in advocating for suffrage, racial and gender equality. Some of these women included Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Maria W. Stewart, Henrietta Purvis, Harriet Forten Purvis, Sarah Remond and Mary Ann Shadd Cary.

Black women, despite their significant reform efforts and activism leading to the ratification of the 19th Amendment, faced additional challenges in racial marginalization and enduring white supremacist tendencies both inside and outside of suffrage organizations.

The trend for white suffragists and white suffrage organizations began to lean toward choosing “expediency over loyalty” when it came to their Black counterparts. The “mainstream” suffrage movement prioritized white supremacist ideologies to increase support for white women’s voting rights over universal suffrage.

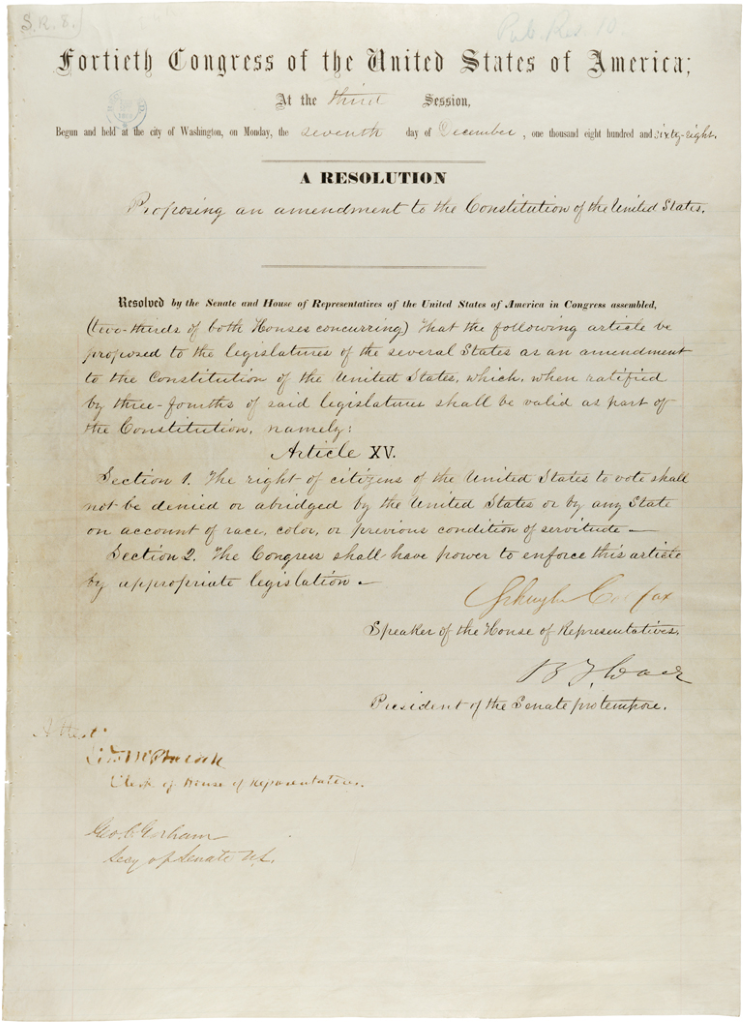

15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, 1870.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Most of the interracial suffrage efforts began to deteriorate with the proposal of the 15th Amendment in 1869, which declared the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The Amendment was ratified in 1870. Many white suffragists felt threatened by Black men receiving the right to vote before white women did.*

Leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) and Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) strongly disagreed with the 15th Amendment, cut ties with organizations who supported it, and formed the National Women Suffrage Association (NWSA). Stanton’s and Anthony’s discriminatory remarks toward Black men and women further severed relationships with Black suffragists, such as Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911).

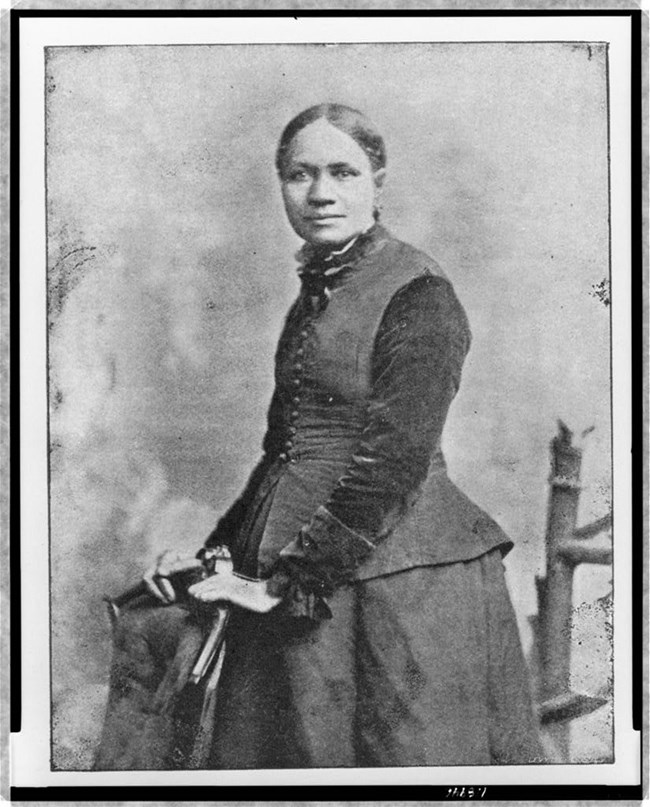

Figure 1. Frances E. W. Harper, c. 1898. Frontispiece of Harper’s Poems

(Philadelphia: George S. Ferguson Co., 1898). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Harper, an abolitionist, suffragist, speaker, educator, poet, writer and one of the first Black women to be published in the United States, supported the 15th Amendment. She joined the new American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), an organization that believed in Black suffrage.

The 15th Amendment serves as the cornerstone for discussions on how race and gender continue to become intertwined in the proposal and eventual ratification of the 19th Amendment. In the South especially, states did not uphold or enforce the 15th Amendment. White leaders knew that the passing of the 19th Amendment would compel the federal government to more strictly enforce the 15th Amendment, so they called for the 15th Amendment to be repealed.

Mary Church Terrell. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954), a founding member and the first president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), argued that “the reasons for repealing the Fifteenth Amendment differ but little from arguments advanced by those who oppose the enfranchisement of women.”

Terrell was respected by many as one of the first African American women to receive a college degree, as well as a national activist for suffrage and civil rights. She joined Ida B. Wells in her efforts to elevate the status of Black women.

Many white suffragists challenged Black women in asking why they need a ballot. Adella Hunt Logan, a Black writer, educator and suffragist, responded to their query:

“If white American women, with all their natural and acquired advantages, need the ballot, that right protective of all other rights; if Anglo Saxons have been helped by it... how much more do black Americans, male and female need the strong defense of a vote to help secure them their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?” - Adella Hunt Logan, Colored American Magazine (1905)

Black woman casting a ballot, c1920.

Courtesy of Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images.

The achievements made by Black suffragists are many and serve as a true testament to the fearless leadership and advocacy displayed on the journey to the ratification of the 19th Amendment. The Black community’s accomplishments are largely overlooked when learning about the suffrage movement and that must change. Women’s suffrage would not have been possible without the efforts of Black women educating, advocating and fighting for racial, gender and political equality.

(*Black men secured the right to vote in 1870 when the 15th Amendment was adopted into the Constitution. Due to a long series of discriminatory legislation after the 15th and 19th Amendments were ratified, the Black community could not freely vote, especially in the South, until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The Act did not solve all voting problems faced by the Black community but continued to challenge state imposed voting restrictions and improved the overall voter turnout.)

Women’s suffrage in the Queen City

North Carolina did not show much support for the suffrage movement until November 1913 when Suzanne Bynum and Anna Forbes Lidell organized the Charlotte Chapter of the Equal Suffrage League (ESL). Only white men and women were admitted to this organization, excluding all persons of color.

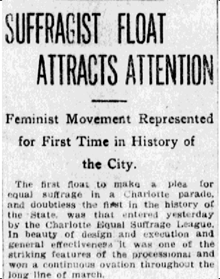

On May 20, 1914, ESL members Suzanne Bynum, Anna Forbes Liddell, Catherine McLaughlin, Jane Stillman, Julia McNinch, Bessie Mae Simmonds and Mary Belle Palmer advocated for women’s suffrage during the May 20 parade, a local holiday celebrating the alleged Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. The unprecedented suffragist float attracted much attention to the suffrage movement.

Image 1: Equal Suffrage League. May 20, 1914. Courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library. Image 2: Charlotte News article, May 21, 1914.

Several months before the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s (NAWSA) president, Carrie Chapman Catt, founded the League of Women Voters during the annual convention. Designed as a nonpartisan, grassroots organization, the League worked to assist the 20 million new female voters in understanding and executing their new civic duties. This organization of women is still active across the nation today, but, as with many other suffrage organizations, has a complex history.

Unfortunately, Catt carried the same racist tendencies as many other white women in the suffrage movement, confirmed by her comment while lobbying to southern senators that “white supremacy will be strengthened, not weakened, by women’s suffrage.” Catt also blocked the Northeastern Federation of Women’s Clubs, a group of Black suffragists, from joining NAWSA to protect the political feelings of white voters.

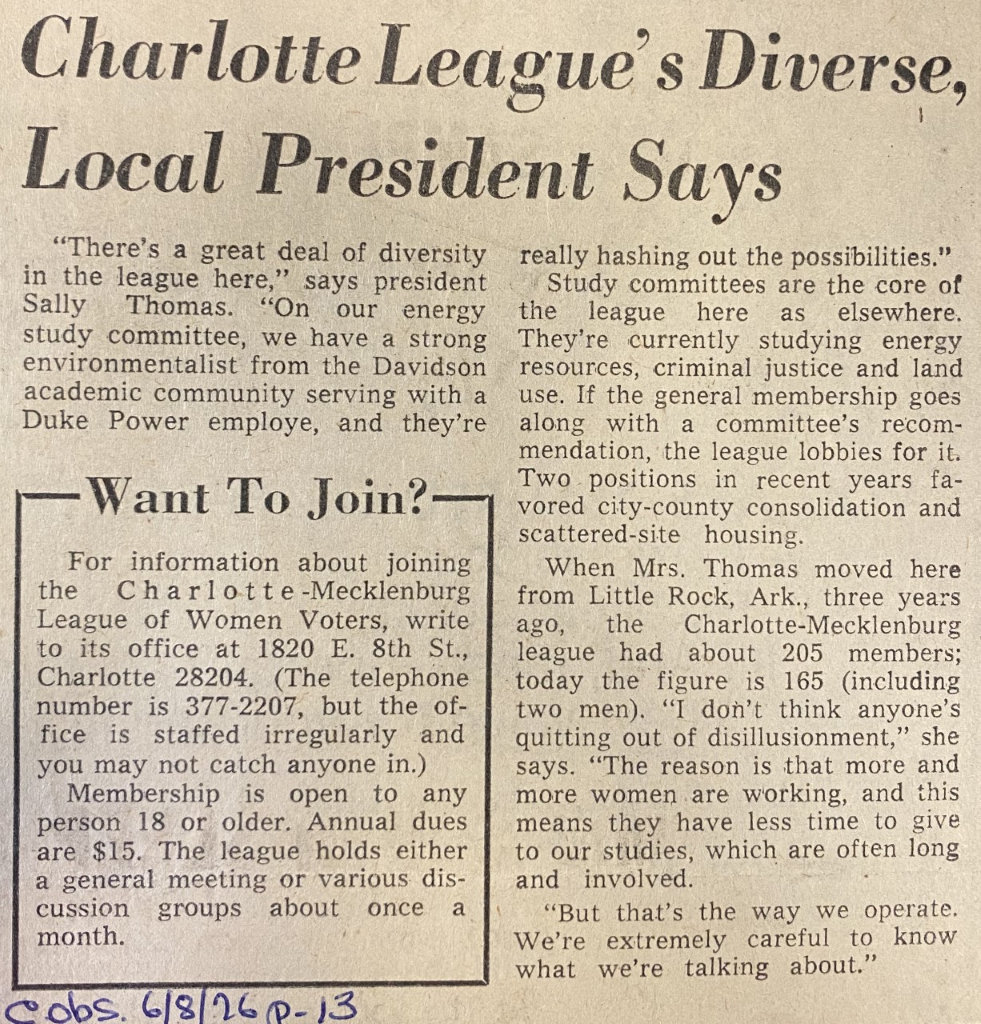

Early on in its history, the League had a different idea of diversity.

Courtesy of the Charlotte Observer, June 8, 1926.

The League of Women Voters has publicly recognized their early unforgiving history and admitted that "African Americans were shut out of the vision of the League,” but, “As we continue to grow our movement, we acknowledge our privilege and must use our power to raise the voices of those who haven’t always had a seat at the table.” During a time of difficult conversations, the League of Women Voters vowed to not only strive for better, but to do better.

Despite the complicated racial and political issues endured by the League early in its history, the organization has proven to be a critical nonpartisan, activist, grassroots organization that values voter education and political and social reform. Women (and men) in the League dedicate their lives and careers to making sure that all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or gender have the tools to elevate their voices and advocate for change. Their mission of empowering voters and defending democracy has led them to become one of the most impactful and successful political groups in the country.

The Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room houses the League of Women Voters Records, which are available for research (with restrictions due to the COVID-19 crisis).

Look Back, Move Forward

“Vote Baby Vote.” Courtesy of Gabriel Hackett, Getty Images.

The theme for Engage 2020 is “Look Back, Move Forward.” Through Engage 2020, the Library is working to tell the incredible stories of how women, particularly women of color, engaged in the suffrage movement and other civic initiatives over the last 100 years.

In order for our nation to move forward, we must look back on our history to better understand the injustices present in our community. Doing so enables us to move forward with a united front, advocating for equal rights for all.

--

This blog was written by Sydney Carroll of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room at Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Charlotte League of Women Voters Records, 1920-2004. Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

Glasby, Heather. “Testing the 15th Amendment: Milton Claiborne Nicholas and the Legacy of the First Black Voters,” Prologue Vol. 48, No. 4 (Winter 2016). Accessed July 2020. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2016/winter/15th-amend-nicholas

Hamlin, Kimberly A. “How racism almost killed women’s right to vote: Women’s suffrage required two consitutional amendments, not one.” June 4, 2019. Accessed July 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/06/04/how-racism-almost-killed-womens-right-vote/

Harley, Sharon. “African American Women and the Nineteenth Amendment.” National Park Service. April 10, 2019. Accessed July 2020. https://www.nps.gov/articles/african-american-women-and-the-nineteenth-amendment.htm

Kase, Virginia. “Facing Hard Truths About the League’s Origin.” League of Women Voters. August 8, 2018. Accessed July 2020. https://www.lwv.org/blog/facing-hard-truths-about-leagues-origin

Logan, Adella Hunt. “Woman Suffrage,” Colored American Magazine 9, no. 3 (September 1905): 487, quoted in Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 60–61

Micals, Debra, Dr. “Mary Church Terrell.” National Women’s History Museum. Accessed July 2020. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-church-terrell

Talbert, Mary B. “Women and Colored Women,” Crisis 10, no. 4 (August 1915): 184.

“The 19th Amendment.” National Archives. Accessed July 2020. https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/amendment-19

"100 Years of League of Women Voters.” Accessed July 2020. https://www.lwv.org/about-us/history

“15th Amendment.” History.com. November 27, 2019. Accessed July 2020. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/fifteenth-amendment