Commemoration of Emancipation by African Americans in North Carolina, 1865-1920

June 16, 2023

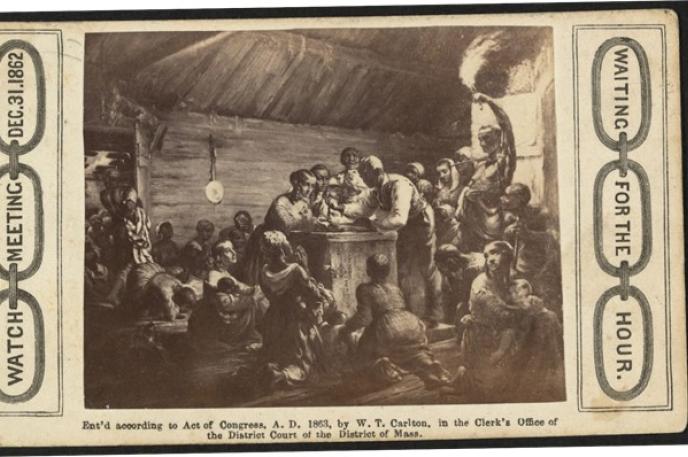

Before there was Juneteenth, there was Emancipation Day: January 1st, 1863, the day the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. The only public celebrations on the first Emancipation Day took place in Northern cities, where persons in flight from slavery gathered to watch for midnight on New Year’s Eve, 1862. With the coming of January 1st, the terms of the Emancipation Proclamation came into effect, and escaped slaves would be delivered from the threat of arrest and transportation to a slave state. The Proclamation stripped slave-owners in rebel states, at least, of the right to reclaim fugitives as stolen property.

On the second anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation – January 1, 1865 – the Civil War was still being fought and Abraham Lincoln was alive and well in the White House. Black people in North Carolina knew better than to celebrate a Proclamation by the Commander in Chief of the opposing side, but New Bern, NC, offered different circumstances. Federal forces occupied the town and they – the Union soldiers – organized and oversaw a celebration of the anniversary that included local freedmen.

The first peacetime celebration of emancipation in North Carolina that was led by the freedmen themselves took place in Wilmington in January of 1866.

The previous month had seen two momentous changes regarding slavery and the law. On December 5th, 1865, the thirteenth amendment had been ratified by enough states to be added to the Constitution of the United States. It made the abolition of slavery permanent throughout the nation. Three weeks later, the voters of North Carolina added an amendment to the state constitution abolishing slavery in the state. These actions closed the door to the possibility of undoing the Emancipation Proclamation, either at the federal or the state level.

On Emancipation Day, 1866, freedmen and freedwomen got their first chance to express their relief at the end of the war and their hope for building new lives after enslavement.

“We understand that a grand celebration by the colored population is to take place on the first of January,” said an editorial in the Wilmington Herald. Indeed, it was. When Emancipation Day came, the Black community of Wilmington turned out, and people from the surrounding rural areas came in to join them.

The rejoicing crowd staged a procession through the streets. They were led by a band and carried banners to show what they believed in: “The Emancipation Proclamation: This We Celebrate,” “Abraham Lincoln, Our Martyred President,” “and “Equal Justice.” This last one expressed the marchers’ demand for recognition of themselves as full citizens of the United States. The 14th Amendment would promise just that, and Congress enacted it later that year.

The Wilmington celebration was built on the model that was pioneered in New Bern and adopted by Black communities in other North Carolina cities: a parade led by a band, an excited crowd of all ages, and speeches. These elements of the celebration would appear every year in towns throughout the state. Enthusiasm for the celebration of Emancipation Day did not wane until the 1920s. By then, according to A History of African Americans in North Carolina by Jeffrey Crow, “younger Blacks began to question the continued commemoration of Emancipation Day.

In Texas, however, the local holiday of “Juneteenth” persisted. It kept alive the idea of a day to celebrate emancipation and became a national holiday in 2021.

- Written by Tom Cole, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room