Part III: the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence meets controversy

May 17, 2019

(Already read Part II? Jump ahead to Part IV.)

NOTE: This post is part three in a four-part series that explores the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Don’t forget to read parts one and two.

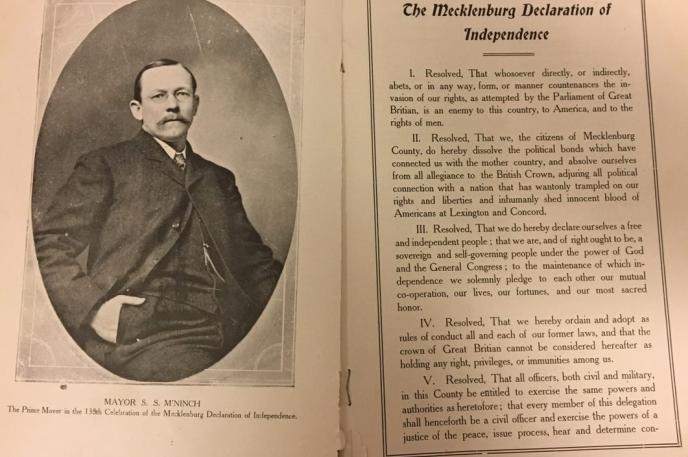

Either these resolutions are a plagiarism from Mr. Jefferson's Declaration of Independence, or Mr. Jefferson's Declaration of Independence is a plagiarism from those resolutions.

—John Adams, August 21, 1819

The Mecklenburg Declaration and the Declaration of Independence had several similar phrases, including "dissolve the political bands which have connected," "absolve ourselves from all allegiance to the British Crown," "are, and of right ought to be" and "pledge to each other, our mutual cooperation, our lives, our fortunes, and our most sacred honor."

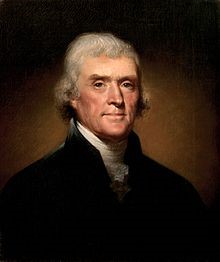

Did Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the American Declaration of Independence, use the Mecklenburg Declaration as a source? Had he seen the Mecklenburg Declaration? Was the language used in both documents common for the day?

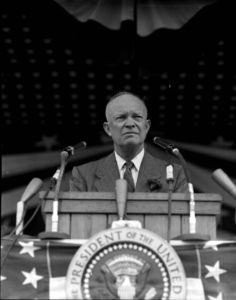

Former President Thomas Jefferson, principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence, suspected that the Mecklenburg Declaration was a hoax. John Adams agreed with Jefferson. When Adams read Dr. Alexander's 1819 article in a Massachusetts newspaper, he was astonished because he had never previously heard of the Mecklenburg Declaration. He immediately assumed, as he wrote a friend, that Jefferson had "copied the spirit, the sense, and the expressions of it verbatim into his Declaration of the 4th of July 1776." Adams had played a role in getting the Continental Congress to declare independence in 1776 and was, therefore, somewhat resentful that Jefferson received most of the praise. Adams sent a copy of the article to get Jefferson’s reaction.

Former President Thomas Jefferson, principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence, suspected that the Mecklenburg Declaration was a hoax. John Adams agreed with Jefferson. When Adams read Dr. Alexander's 1819 article in a Massachusetts newspaper, he was astonished because he had never previously heard of the Mecklenburg Declaration. He immediately assumed, as he wrote a friend, that Jefferson had "copied the spirit, the sense, and the expressions of it verbatim into his Declaration of the 4th of July 1776." Adams had played a role in getting the Continental Congress to declare independence in 1776 and was, therefore, somewhat resentful that Jefferson received most of the praise. Adams sent a copy of the article to get Jefferson’s reaction.

Jefferson replied that, like Adams, he had never heard of the Mecklenburg Declaration before. Jefferson found it curious that historians of the American Revolution, even those from North Carolina and nearby Virginia, had never previously mentioned it. He also found it suspicious that the original was lost in a fire and that most of the eyewitnesses were now dead. Jefferson wrote that while he could not claim for certain that the Mecklenburg Declaration was a fabrication, "I shall believe it such until positive and solemn proof of its authenticity shall be produced."

Jefferson's argument, Adams wrote in reply, "has entirely convinced me that the Mecklenburg [sic] Resolutions are a fiction.” Thus began centuries of controversy.

North Carolina Senator Nathaniel Macon collected eyewitness testimony to the events described in the article. The then elderly witnesses did not agree with every detail, but they generally corroborated the story that a declaration of independence had been publicly read in Charlotte, although they were not all certain about the date. Perhaps most importantly, 88-year-old Captain James Jack was still alive and was able to confirm that he delivered a declaration of independence to the Continental Congress that had been adopted in May 1775.

Enjoying reading about the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence? Stay posted for installment three of this four-part series which leads up to Meck Dec Day on May 20. Expect the next installment in this series on Monday, May 20.

WELCOME! – The fun begins with an awe-inspiring collection of MR. POTATO HEAD parts and accessories as well as an anthology to depict the character’s wild adventures.

WELCOME! – The fun begins with an awe-inspiring collection of MR. POTATO HEAD parts and accessories as well as an anthology to depict the character’s wild adventures. SPUD QUEST – While on an archeological dig in search of the statue of King Tato, visitors will need to decipher “tatoglyphs” and solve mazes to find the statue’s secret caché. Guests will use special maps to explore the treasure chamber and excavate the dig site to uncover fun artifacts from the King’s past, while reconstructing the King’s crown and weighing the discoveries in MR. POTATO HEAD’s research tent.

SPUD QUEST – While on an archeological dig in search of the statue of King Tato, visitors will need to decipher “tatoglyphs” and solve mazes to find the statue’s secret caché. Guests will use special maps to explore the treasure chamber and excavate the dig site to uncover fun artifacts from the King’s past, while reconstructing the King’s crown and weighing the discoveries in MR. POTATO HEAD’s research tent. SPUD SAFARI – While roaming jungles with MR. POTATO HEAD, visitors can enjoy a pretend mudslide or venture inside a cave in search of mysterious objects. Guests should listen carefully to identify sounds in the jungle, discover camouflaged and hidden creatures, and gain a different perspective when they use special lenses and cameras to see the world through the eyes of silly birds, bugs and animals.

SPUD SAFARI – While roaming jungles with MR. POTATO HEAD, visitors can enjoy a pretend mudslide or venture inside a cave in search of mysterious objects. Guests should listen carefully to identify sounds in the jungle, discover camouflaged and hidden creatures, and gain a different perspective when they use special lenses and cameras to see the world through the eyes of silly birds, bugs and animals. The summer exhibit at ImaginOn is funded through the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library’s Humanities Endowment Fund, with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The summer exhibit at ImaginOn is funded through the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library’s Humanities Endowment Fund, with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

While the Library offers numerous programs to help with digital literacy, this program is unique. DigiLit Community takes the curriculum, staff and devices into the community to reach those who may face barriers in accessing a traditional library facility and program. Thanks to a new gift from the Van Every Foundation to support two portable computer labs, DigiLit will be in the community even more.

While the Library offers numerous programs to help with digital literacy, this program is unique. DigiLit Community takes the curriculum, staff and devices into the community to reach those who may face barriers in accessing a traditional library facility and program. Thanks to a new gift from the Van Every Foundation to support two portable computer labs, DigiLit will be in the community even more. It also offers a structured sequential curriculum (as opposed to a one-time class) and individualized practice time to make the sessions relevant to the student's needs.

It also offers a structured sequential curriculum (as opposed to a one-time class) and individualized practice time to make the sessions relevant to the student's needs.

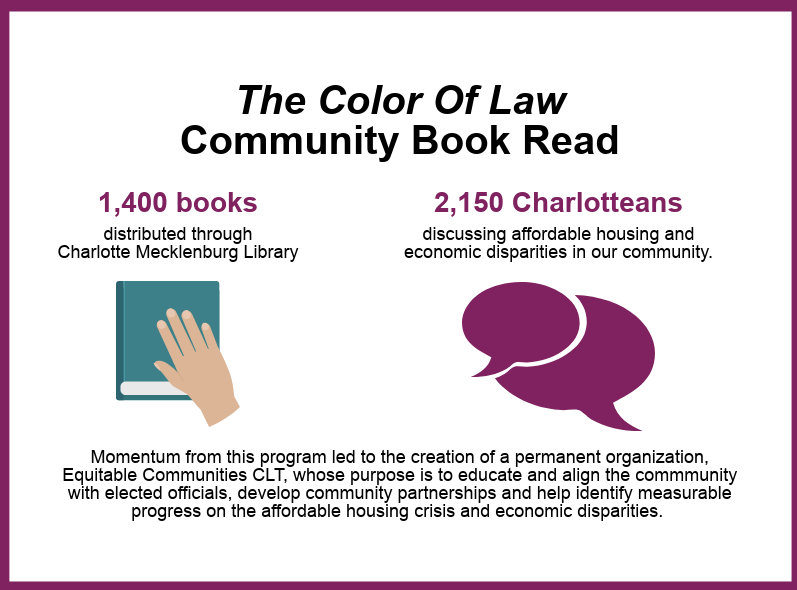

On a Monday winter night in January, 1,200-1,500 people of various racial, socioeconomic, age, and ZIP code backgrounds packed into a congregation and overflow of First Baptist Church West to see Richard Rothstein and local community members discuss our affordable housing crisis and Rothstein’s book The Color of Law, detailing our government’s segregation of our nation. This response doesn’t occur without Charlotte Mecklenburg Library freely distributing the book at their various regional locations throughout the community.

On a Monday winter night in January, 1,200-1,500 people of various racial, socioeconomic, age, and ZIP code backgrounds packed into a congregation and overflow of First Baptist Church West to see Richard Rothstein and local community members discuss our affordable housing crisis and Rothstein’s book The Color of Law, detailing our government’s segregation of our nation. This response doesn’t occur without Charlotte Mecklenburg Library freely distributing the book at their various regional locations throughout the community.

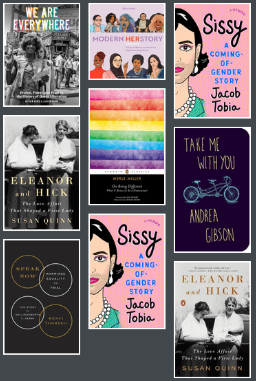

On June 28, 1969, the New York Police Department raided the historic Stonewall Inn, a gay bar, in Manhattan. Police raids on gay establishments were common in the 1950s and 1960s when social and political anti-gay and homophile efforts flourished. Gay bars were places of refuge where LGBT people could safely be in community without fear of public ridicule or police aggression. However, on that fateful morning, patrons of the Stonewall Inn decided to fight back against the police and the injustices against them. The week-long riots, which coincided with the civil rights and feminist movements, became the catalyzing moments that birthed the gay liberation movement.

On June 28, 1969, the New York Police Department raided the historic Stonewall Inn, a gay bar, in Manhattan. Police raids on gay establishments were common in the 1950s and 1960s when social and political anti-gay and homophile efforts flourished. Gay bars were places of refuge where LGBT people could safely be in community without fear of public ridicule or police aggression. However, on that fateful morning, patrons of the Stonewall Inn decided to fight back against the police and the injustices against them. The week-long riots, which coincided with the civil rights and feminist movements, became the catalyzing moments that birthed the gay liberation movement. Just six months after the uprising at Stonewall, numerous grassroots gay and human rights organizations began to form across the U.S. such as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). Since the Stonewall riots, the LGBT community has made many strides against injustice. In October 1979, the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights took place in D.C. which drew an estimated attendance of 75,000-125,000 supporters. On March 2, 1982, Wisconsin became the first U.S. state to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation and in April 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that states cannot ban same-sex marriage. For a current list of LGBT rights, milestones and fast facts

Just six months after the uprising at Stonewall, numerous grassroots gay and human rights organizations began to form across the U.S. such as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). Since the Stonewall riots, the LGBT community has made many strides against injustice. In October 1979, the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights took place in D.C. which drew an estimated attendance of 75,000-125,000 supporters. On March 2, 1982, Wisconsin became the first U.S. state to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation and in April 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that states cannot ban same-sex marriage. For a current list of LGBT rights, milestones and fast facts

t all ends with the eating of sweet buns served with milky coffee or tea.

t all ends with the eating of sweet buns served with milky coffee or tea.