This blog was written by Sydney Carroll, archivist of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

*sensitive content warning*

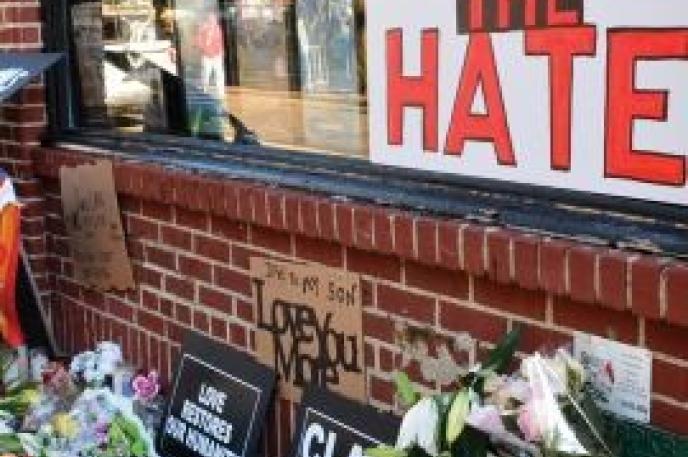

“You’ve found answers in four days that I couldn’t find in forty years. You did more than research...you found my family. We gave them back the stories that were stolen from them.”

Hidden inside the census, slave schedules, deeds, and vital records, Kevin Graham finally learned where he came from. It was not as simple to trace his lineage as one would think, given the intentional erasure of Black names in American historical records.

Kevin called the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room to find answers he had been searching for over the past 40 years. He hoped to link his maternal third great grandfather, Wesley Shipp (1817-1875), to white plantation owner, Bartlett Shipp (1786-1869). Kevin believed that Wesley (or possibly Wesley’s parents) was the first Black Shipp but could not find the records to prove it.

He also wanted to link his paternal great grandfather, George Graham (1840-c1910), and great grandmother, Violet Luckey Graham (1840-c1910), to Elmwood Plantation. Both the Shipp and Graham families (Black and white) have roots in Lincoln County, North Carolina.

To put it simply, Black genealogy is a beast. It is not only difficult to conduct genealogical research due to the lack of historical records for Black Americans, but it is also an emotional road to travel. Many times, the traumatic reminder of slavery is woven into their DNA, resulting in more questions than answers.

With the assistance of Sydney Carroll, archivist of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Kevin said that together we “made cracks in the brick wall” he hit after decades of searching for answers. Laughing, he described his ancestry as a “family bush” instead of a family tree because his lineage is wider than it is tall. After all that time and trauma, it would be understandable to hold some anger and resentment. But Kevin explained that, “There’s no hard feelings. I just want to know.”

WESLEY SHIPP | The First Black Shipp?

Accidental Discoveries

Kevin first inquired if his third great-grandfather, Wesley, was the first Black Shipp. In the initial stages of researching the Shipp line, we did not find concrete, historical evidence to support this theory. However, while conducting historical property research on Wesley's white enslaver, Bartlett Shipp, we “accidentally” discovered a deed dated April 10, 1852, that specifically named Wesley, his wife, Winnie Abernathy Shipp (1820-1905), and five of their children for sale to pay off his debts to his father-in-law, Peter Forney (1756-1834). [1]

Lincoln County, North Carolina Register of Deeds, Deed Book 42:204

It is unclear when Bartlett Shipp first enslaved Wesley, but census records and deeds indicate that it could have been as early as 1822 after purchasing 249.5 acres of land from Peter Forney to build his estate, The Home Place. [2] At this time, Wesley would only be about five years old, so it is possible that Bartlett’s intention was to enslave his mother and/or father and bought Wesley along with them. It is also possible that Bartlett purchased Wesley later in life as a young adult.

Bartlett was born in 1786 in Stokes County but moved to Lincoln County to study law under Joseph Wilson, making him the first Shipp in Lincoln County. These discoveries lead us to believe that Wesley or his mother/father were the first Black Shipps.

Winnie Abernathy Shipp (1820-1905). Courtesy of Ancestry.com

We are still unsure when Winnie, Wesley’s wife, became enslaved at the Shipp plantation. It is possible that the Abernathy family first enslaved Winnie since her son’s death certificate listed “Abernathy” as her maiden name.

Death Certificate for Joe Shipp, June 29, 1928. [3]

Several public family trees on Ancestry list Turner Abernathy (1763-1845), a white farmer, as her father, but no documentation exists to prove it. Turner married Susannah Marie Forney (1767-1850) in 1784, so it is also possible that the Forney family enslaved Winnie and/or her mother, and later sold her to Turner. Or, Turner enslaved Winnie’s mother, whom he raped and impregnated, resulting in the birth of Winnie. This theory would explain why Winnie and her children are described as “mulatto” in the 1870 census. Enumerators assigned “mulatto” to individuals who had mixed Black and white ancestry, a result of the horrendous acts against enslaved Black women by their enslavers.

Clues in the Census

Census records that predate 1850 only include the head of household’s name and the number of people ("free white,” “free colored,” or “slave”) living in the household. Similarly, “slave schedules” recorded enslaved individuals separately during the 1850 and 1860 census. Most schedules do not record the enslaved person’s name, but include information relating to their age, gender, and “color.” Below is a general outline of the 1830-1860 census records for Bartlett Shipp:

- 1830 census-1 male aged 10-23 (Wesley, age 13); 4 females aged 10-23 (Winnie, age 10) [4]

- 1840 census-7 males aged 10-23 (Wesley, age 23); 6 females aged 10-23 (Winnie, age 20) [5]

- 1850 slave schedule-1 male aged 33; closest female is aged 26 [6]

- 1860 slave schedule-0 male aged 43; 0 female aged 40* [7]

*According to the deed, Bartlett Shipp sold Wesley, Winnie, and their five children in 1852, so this data verifies that they were no longer enslaved by Bartlett in 1860.

Unfortunately, early census records require genealogists to infer as to whether the person of interest is included in the stated age range or not. Because of the deed that mentions Wesley and Winnie by name, we have definitive evidence of their enslavement by Bartlett Shipp in 1852.

Wesley, Winnie, and their children in the 1870 Census [8]

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that “all persons held as slaves [in the rebellious states] are, and henceforth shall be free.” [9]

Wesley appears as a “free” man in the 1870 census with Winnie and nine of their children. They lived in Catawba Springs Township, which is about 14 miles from where the Shipp plantation once existed. No other Black Shipp families lived nearby until the 1900 census, when we saw Winnie’s son, William Shipp, and granddaughters, Mary and Agnes Caldwell, living with her in the house she owned.

Life On The Home Place

Rural Delivery Routes Map, Lincoln County, North Carolina, 1851. [10]

Wesley, Winnie, and their children were enslaved on the Shipp plantation, known to the family and community as “The Home Place.” [11] In August 1822, Bartlett purchased 249.5 acres of land from his father-in-law, Peter Forney, for $1,000 (area circled in red). [12] There is evidence that this is the same land that Bartlett built The Home Place, but there is no definitive evidence due to long lost boundary descriptions written into the deed, such as “the fish trap.” [13]

Wesley's family likely farmed cotton at The Home Place, but the Lincoln Courier also suggested that the land had “a quantity of gold, as well as iron.” [14]

“I wanted to know that all of my ancestors made a difference,” Kevin explained. “It strengthens me to know what my ancestors went through. Someone had to survive the boat ride, stay chained up, not risk their life running. My people had to survive Jim Crow, redlining, and the Civil Rights Movement. If they didn’t, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.”

GEORGE AND VIOLET GRAHAM | Life at Elmwood Plantation

“I saw George on Zennie’s death certificate. My grandfather was born in 1876, so it wasn’t a reach to think that [his father] could have been enslaved...I googled “Graham Plantation,” which is when I learned about Elmwood Plantation.”

In addition to researching his maternal line, Kevin also asked for help in linking his great grandfather, George Graham, on his paternal line to Elmwood Plantation. White plantation owner John Davidson Graham (1789-1847) built the Graham House, also known as Riverview, between 1825-1828 with the use of forced labor of those he enslaved. [15] Elmwood Plantation sat on 1,200 acres of land near the end of present-day Ranger Island Road in Lincoln County. [16]

We began our research by reading John Davidson Graham’s will dated 1847, where we found George listed by name on the second page. John bequeathed George to his son, Robert Clay Graham. At that time, George was 7-10 years old.

The 1870 census was the first census that recorded the formerly enslaved as people instead of property. In this census, George is listed as a farm laborer married to Violet Luckey Graham, with whom he shared a 3-year-old daughter named Lizzie.

"The success of Elmwood made the plantation owners prideful and boastful, which gave them the desire to preserve historical documentation to cement their legacy. Thus, it has given me a small glimpse into mine, and for that reason I am thankful and blessed.”

The 1900 census states they had been married for 38 years. [17] This means that George and Violet were married in 1862, three years before slavery’s end was enforceable by Union troops in the south. This ties Violet to the Graham family through her marriage to George while he was still enslaved by Robert Clay Graham. [18] If Violet was not enslaved by the Graham family before her marriage to George, the year 1862 is when her (and likely her mother's) connection to Elmwood Plantation began.

On old censuses, enumerators went door to door, so now, present-day researchers can get an idea of neighboring families by looking at who was listed above or below them on the census record. A few rows above George and Violet is Clay Graham--presumably, Robert Clay Graham, son of John Davidson Graham--who is listed as a farmer.

“Because of you I met George, his father, his mother. Violet and her mother. Their children... [Violet and George] are still family names. It matters. The small details matter.”

In Clay's household, a 60-year-old Black woman named Lizzie Luckey was listed as a domestic servant--an interesting coincidence that George and Violet's daughter's name was Lizzie, and that Lizzie's (the older Black woman) last name was Luckey, which matched Violet's maiden name.

The 1880 census shows an Elizabeth Alexander, described as the mother-in-law to the head of the household, living with George, Violet, and their children. [19] This finding confirmed that the Lizzie Luckey on the 1870 census in Clay's household was, in fact, Violet's mother. We believe that Alexander was Lizzie’s maiden name because she was born in Maryland, which is where the well-known Alexander family of Charlotte migrated from in the mid- to late- 18th century.

“I reached the pinnacle. I’m on the mountain top. I am a unicorn. Only 3% of African Americans can trace their lineage back to Africa. I found my way home. I am an American, but now I know the road of how I got here.”

As if he could not be more excited about our findings, we discovered that, according to the 1880 census, George’s father was born in Africa. [20] This is an extremely rare find, as only a small percentage of Black genealogists can trace their lineage directly to Africa.

SHIPP’S LANE AND GRAHAM ROAD | Intersection of Family History

“One of the white Graham descendants wanted to talk to my aunt, but the trauma was still so fresh that she couldn’t. Aunt Zannie worked in the same field that George probably worked in.”

Maps of land surrounding Elmwood Plantation [21] [22]

Shipp’s Lane and Graham Road intersect near the original location of Elmwood Plantation, before Duke Power Company dammed the Catawba River to create Lake Norman. “Grandma Ida lived on Shipp’s Lane and our church was off Graham Road. I connected the two in my head knowing that my people were probably enslaved.” He continued, “It’s amazing that I see Graham Road and it means something to me. I see the name ’Shipp’ with two p’s and it means something to me.”

Bartlett Shipp’s plantation, The Home Place, sat approximately 7 miles away from this intersection, but he and his descendants owned quite a bit of land throughout Lincoln County. “It’s a puzzle that I didn’t even know connected,” Kevin said with disbelief.

“We may have gotten our freedom in 1863, but I grew up going to church down the street from where our enslavers went. So really, I was still on their land.”

Every Sunday morning as a child, Kevin and his family drove past Graham Road on their way to Ebenezer United Methodist Church. Kevin’s father, Zemerie, helped construct the new building, but Kevin recalls the “old white building” and cemetery across the street, where many of his family members are buried.

Ebenezer is located less than one mile from Unity Presbyterian Church, the church that John Davidson Graham and his family attended and are buried at. It is possible that Kevin’s enslaved ancestors also attended Unity, as people who were enslaved were permitted to sit in a designated area in the back pews.

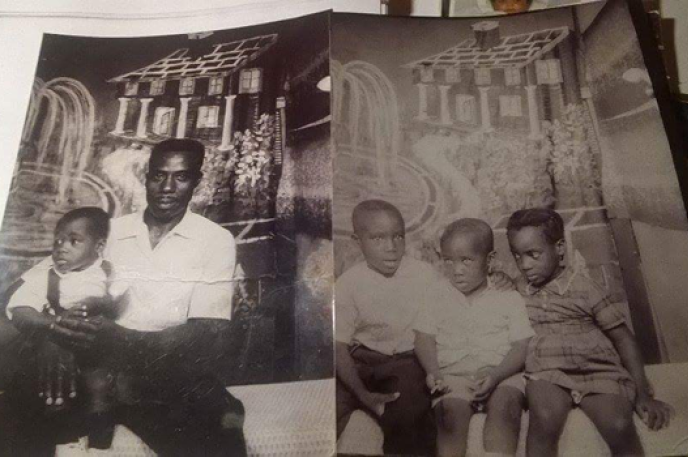

Wendell (brother) and his mother, Vaneva Shipp Graham, at Camp Meeting, c1962

“People say it’s been a long time, but it hasn’t really been much time at all. My father sharecropped. My mother picked cotton. I lived through the modern Civil Rights Movement. I was living and breathing as they were marching. Compared to them, I live my life with no limitations.”

THE GRAHAMS OF TODAY | Living in the Legacy

This We’ll Defend:

Kevin at Fort Jackson during Family Day, c2016

George’s ancestors spent most of their lives defending the country that legally enslaved them just two generations before. Kevin, his older brother, his father, and his five uncles all proudly served in the United States Army. “I served for 27 years, 9 months, and 8 days.” He continued, laughing, “but who’s counting? It was an honor.” Kevin retired from the Army as a Sergeant First Class.

Zemerie Graham, Private First Class, 1942

“My father, Zemerie, achieved [military] awards higher than when I served. At the time, a colored man in the United States Army received awards higher than I received in 27 years of service, but he never got promoted based on color of his skin.”

“My father had different rights as a Black man in America than I have as a Black man in America. My father was better at everything he did. I benefit from the changes he made. My father was so patriotic. The way he loved his country, and I understand why. That’s why I love this country.”

Kevin serving in Tikrit, Iraq, c2005

Kevin continued, “People called my father “Little Soldier,” and he called my brother that too. Our family is known for service. We truly love this country. None of what I’ve learned takes away from that--it actually adds to it. George was a hard worker and had dreams of being free.”

Tucker’s Grove Camp Meeting Ground

Kevin and his family at Camp Meeting, c1967

Left to right: Stephen (brother), Zemerie (father), Wendell (brother), Andreá (sister), and Kevin

Founded in the first half of the 19th century by the Methodist Episcopal Church, Tucker’s Grove Camp Meeting served as a religious site for the spiritual crusade and renewal of the enslaved population. Camp meetings continued “after the abolition of slavery and has been operating continuously since 1876 as an A.M.E. Zion camp meeting site.” [23] Wesley, Winnie, George, and Violet may have attended a camp meeting in their lifetime. We can only wonder if their paths crossed.