Bookmobiles are an effective way to provide equitable access to library resources and services in rural communities. These “libraries on wheels” visit schools, retirement centers, and other hard-to-reach communities that may otherwise not have access to a library.

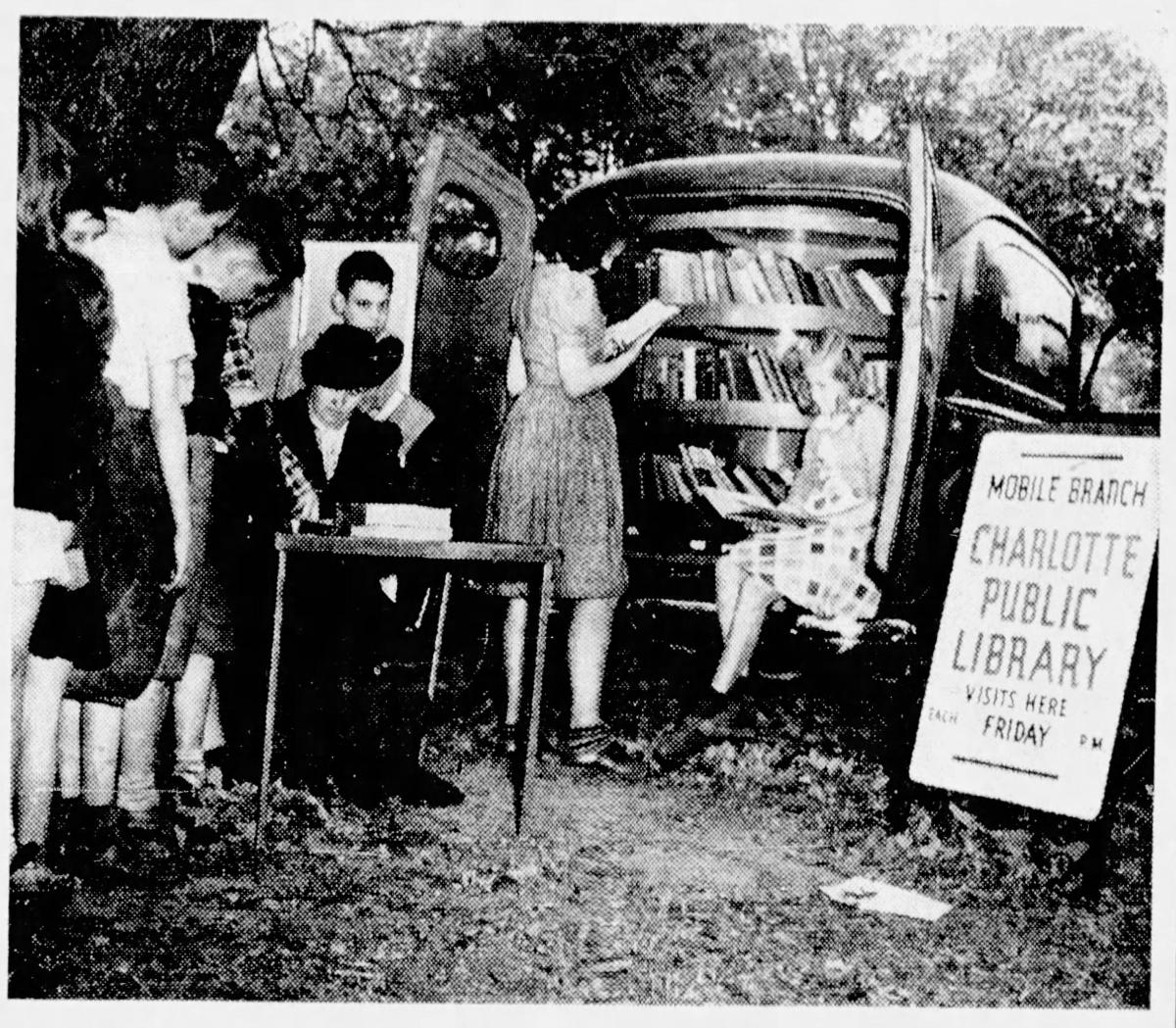

Colorized image of the Public Library of Charlotte’s bookmobile, 1966

Historical Context of the Bookmobile Program

“...the bookmobile rolls along through this rural State, and in its wake wells of water for thirsty minds spring up in the desert...” -Charlotte Observer, January 17, 1937

In 1937, nearly two million North Carolina residents lived in “literary deserts,” areas where books and other reading materials are difficult to obtain. Only 87 public libraries existed in the state at that time, with a combined collection of 744,369 volumes. In response to these startling statistics, The Citizens Library Movement sought to improve and create access to library books through a mobile library service. They partnered with the North Carolina Library Commission to request $150,000 in state funds to fuel their efforts.

State aid not only supported the mobile library program but also covered operational expenses for libraries that could only afford to stay open for several hours a week. The funds helped increase and stabilize collection management budgets as well. [1]

Where the Rubber Meets the Road, 1937-1942

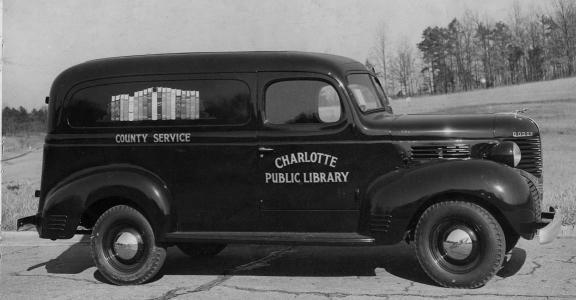

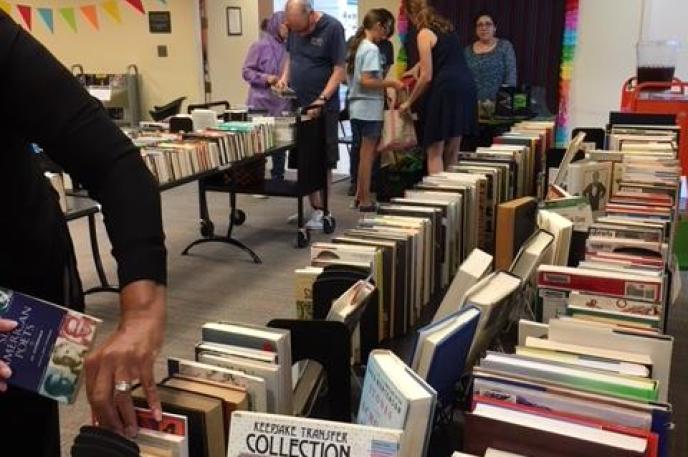

Charlotte Public Library bookmobile, c1937

“...And there are those who would stand out and shade their eyes down the dusty roads and watch for the advent of a bookmobile with anticipation as keen as a kid looking for Santa Claus.” -Charlotte Observer, February 4, 1939

Charlotte's first bookmobile was introduced in December 1937 under the leadership of James E. Gourley, Director of the Charlotte Public Library. The North Carolina Library Commission funded a two-month trial of the service, which allowed library users to borrow “as many books as your family can read in two weeks.” The bookmobile stacked its shelves with approximately 1,000 books from the central branch and journeyed to rural areas, such as Croft, Caldwell, Cornelius, Davidson, and Huntersville, with the hope of extending services to other rural communities after the two-month trial ended. [2]

Gaston County heavily influenced the adoption of the mobile library in Mecklenburg County, proving the importance of “the distribution of books by bookmobile to every nook and cranny of the county,” a conclusion also made by the Charlotte Public Library. [3]

Hotel Charlotte, 1928. Photo courtesy of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

The mobile library experiment proved to be successful, as the Charlotte community fiercely loved the bookmobile. In March 1938 after the trial ended, Governor Hoey addressed a group of “library enthusiasts” from twenty-eight North Carolina counties at Hotel Charlotte. During this meeting, notable speakers, including Charlotte Public Library’s James E. Gourley, requested an annual sum of $300,000 for two years to “equalize public library service in the State.” [4]

Governor Hoey used the state’s shocking illiteracy rates as the driving argument for the continuation of the mobile library service, which visited the rural communities where illiteracy rates were highest:

“Since more than one half of the State’s population live in the rural communities, anything that will increase the reading in those communities will be of tremendous value...and the extension of adequate library facilities into the rural areas will do much toward advancing the interests of North Carolina.” - Governor Hoey, Charlotte Observer, March 27, 1938

Successful in their efforts, the bookmobile program continued. Charlotte Public Library received two bookmobiles. By the end of 1938, the Library established 37 deposit stations in homes and stores around Mecklenburg County. [5]

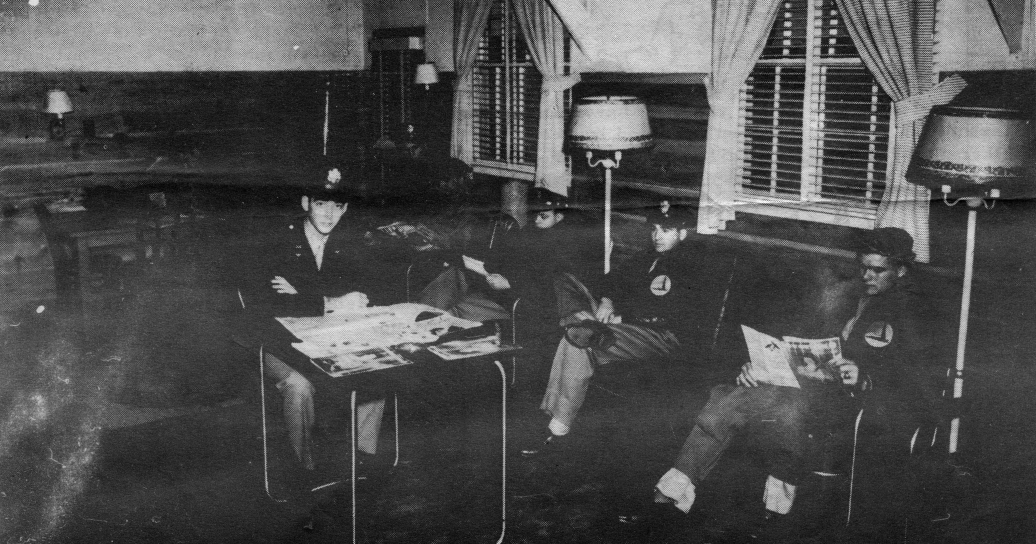

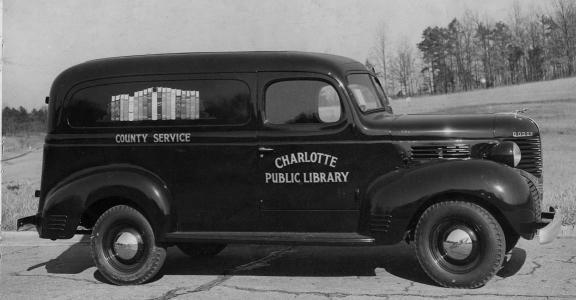

Flying Officers reading on base, November 1942. Photo courtesy of Morris Code, Vol.1, No.17.

“If the Charlotte airbase soldiers become stoop-shouldered and begin wearing horn-rimmed glasses, you can blame the bookmobile...” -Charlotte Observer, September 17, 1941

In addition to serving rural communities, the Library’s bookmobile also served soldiers at the airbase on the outskirts of Charlotte as part of the “Keep ‘em Reading” campaign. (The airbase became known as Morris Field in 1942 to honor Major William C. Morris.) This bookmobile, provided by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in July 1941 and driven by Librarian Carolyn Gregory, was one of two bookmobiles used by the Library at that time. The military men appreciated Gregory’s memory of their names and book preferences. She frequently mentioned the airbase was her favorite stop of all. Her nickname eventually became “Ma,” a name and role she cherished at the base. [6]

The bookmobile visited the airbase every Wednesday and Saturday. Among the most popular books included: “adventure novels of Zane Grey and James Oliver Curwood, the flashing swordplay of Rafael Sabatini, travel, and textbooks in trigonometry, geometry, physics, radio, electricity, history, and Spanish grammar.” [7]

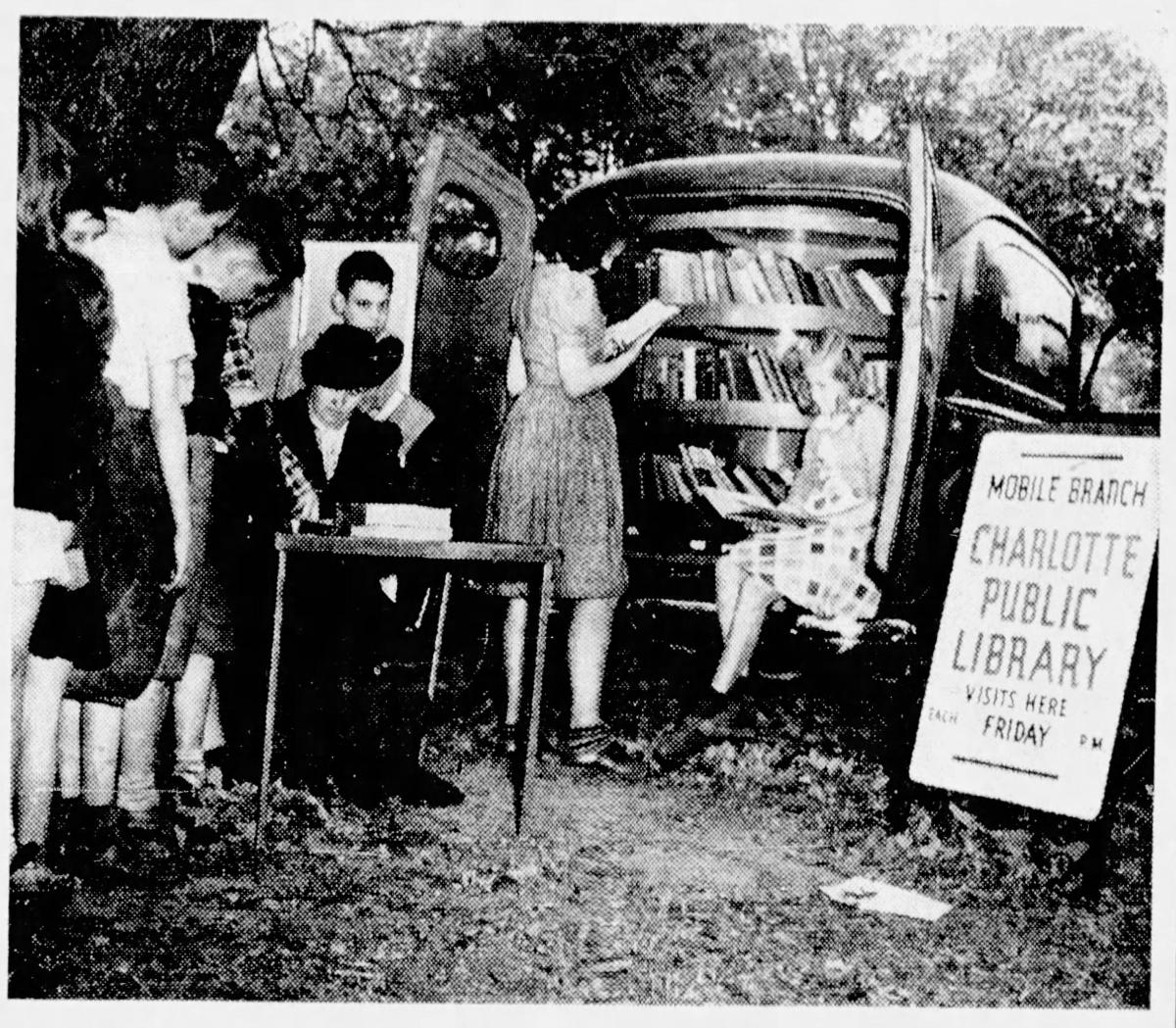

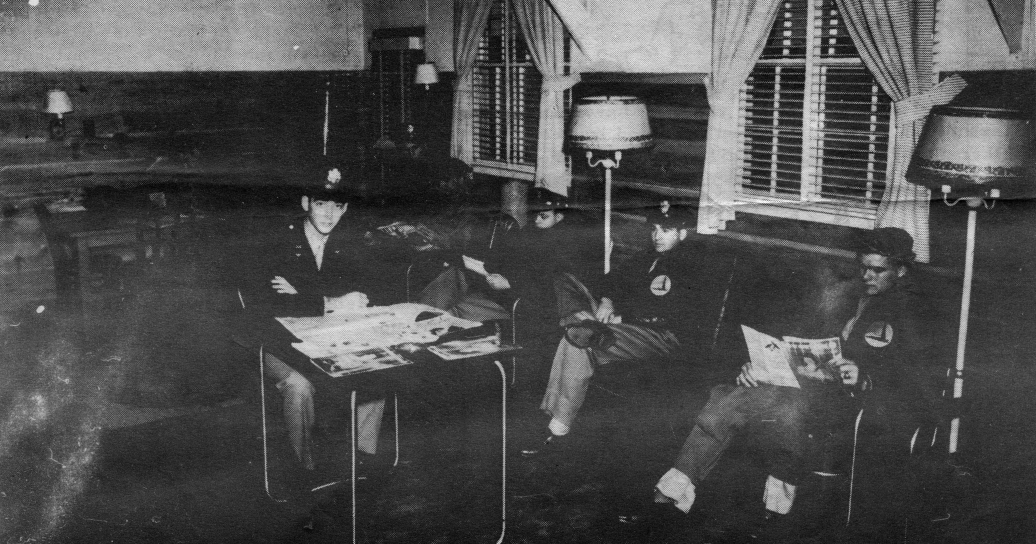

Photo courtesy of the Charlotte Observer, November 30, 1941.

Bookmobiles greatly increased the circulation of the Library’s materials. During the week of November 20, 1941, alone, circulation nearly doubled, thanks to Library Director Hoyt Galvin placing signs that said “Mobile Branch, Charlotte Public library, Visits Here” along the bookmobile’s regular routes. [8] From 1937-to 1941, nearly 7,000 books circulated due to the efforts of the mobile library service. [9]

The winter months proved more difficult for the bookmobile due to icy road conditions. Because the mobile library was a “fresh air business,” Library staff had to get creative when dealing with windy weather. Librarian Carolyn Gregory and Director Hoyt Galvin designed a makeshift wind-breaking device to place behind the card table she set up at each stop while on duty. It consisted of three fire screens and an army blanket. [10]

Rocky Road, 1943-1948

In October 1942, the WPA withdrew the bookmobile used by the Charlotte Public Library for 15 months because of WPA staff shortages and increasing demand from other WPA-related projects. The bookmobile had performed wonderfully in the Charlotte community, logging hundreds of new cardholders and thousands of borrowed books. [11]

Several months later in January 1943, the Women’s Auxiliary Board of Charlotte Memorial Hospital purchased a bookmobile; the Library supplied the books, and the Auxiliary provided volunteer drivers. [12] By April 1945, the Auxiliary volunteers donated a portion of nearly 9,000 hours (shared among receptionists, a sewing group, and the chapel committee) to the Charlotte Public Library’s bookmobile service. [13]

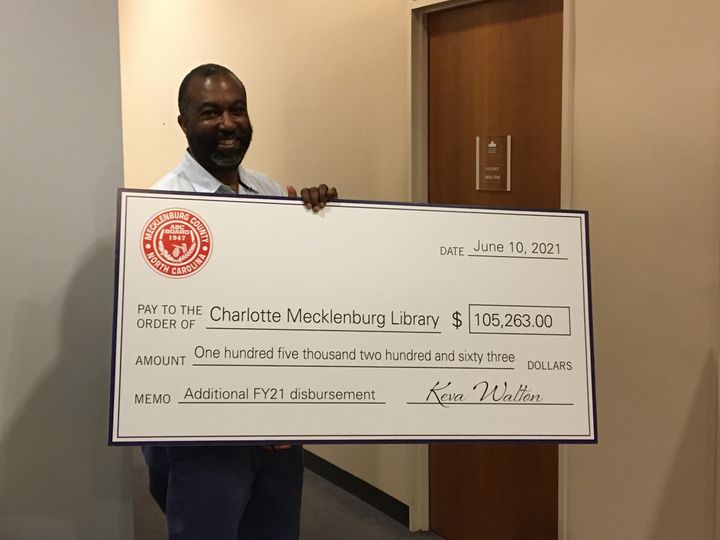

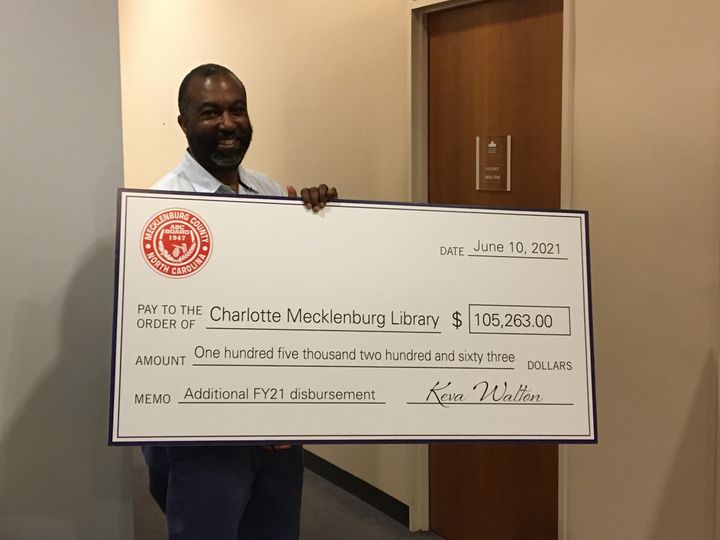

Marcellus Turner, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library CEO/Chief Librarian, with a check from the Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission, June 2021. Photo courtesy of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

The General Assembly authorized an election in 1947 for Mecklenburg County to vote for the Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC) department to contribute five percent of its profits to the Library. The Library saw its first check-in in October 1948, which ultimately funded the purchase of two bookmobiles in 1949. Both bookmobiles cost a grand total of $27,500. [14]

One of the bookmobiles replaced the nine-year-old bookmobile lovingly named Puddle-Jumper, and the other was designated for the Black community. [15] The Library still receives an annual payment from the ABC department to this day.

Bookmobiles for All, 1948-1966

Brevard Street Library, 1944. Photo courtesy of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

Library Director Hoyt Galvin hoped to use the additional funds from the ABC department to improve the Brevard Street Library (1905-1961), the first public library for the Black community in the state. He hired Allegra Westbrooks, the first African American public library supervisor in North Carolina, in 1947.

At that time, only two Black libraries existed in Mecklenburg County--Brevard Street and its “sub-branch” on Oaklawn Avenue. Ms. Westbrooks advocated for the purchase of a bookmobile for the Black community, a dream that came true on December 5, 1949. [16]

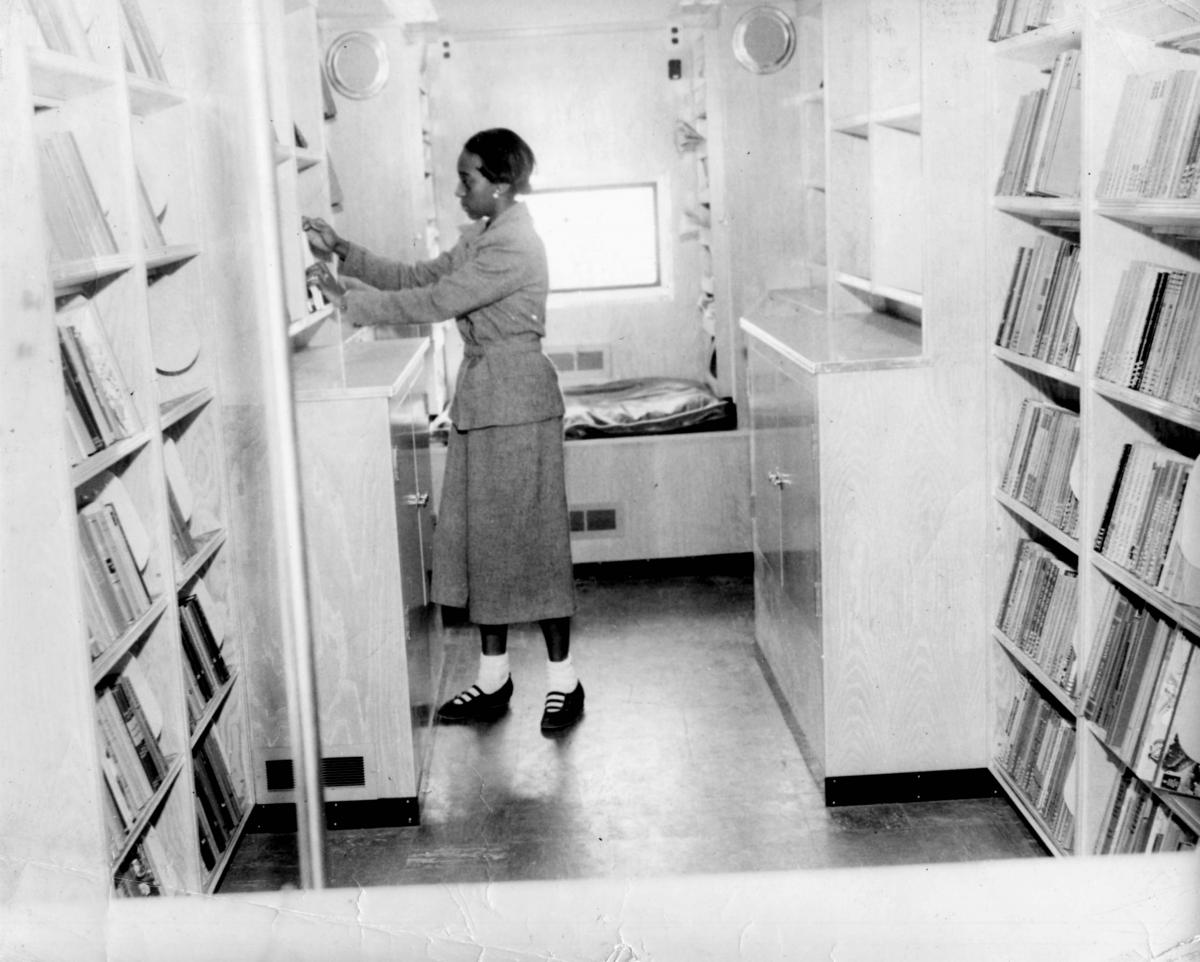

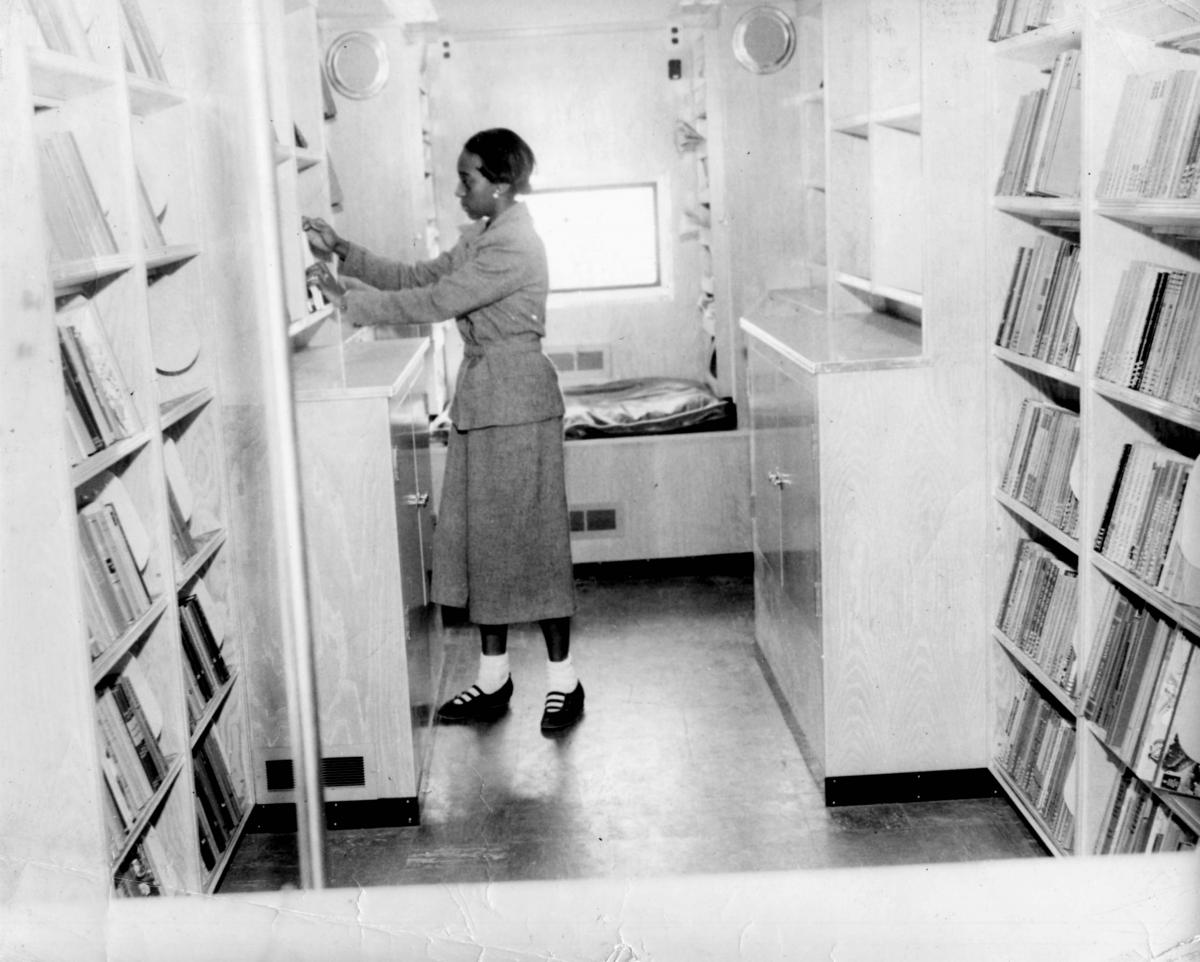

Interior of the bookmobile, 1966. Photo courtesy of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

The bookmobile had the capability to handle about 3,000 books and was fully operational with adequate lighting, reading space, and enough power to project motion pictures. [17] Ms. Westbrooks' proposed bookmobile route included stops at 12th and Alexander Streets, West Hill and Mint Streets, Beatty’s Ford Road and Mattoon Street, Grier Heights, Statesville Terrace, York Road, and multiple other predominately Black neighborhoods in the county. [18]

Colorized image of the PLCMC bookmobile, 1966. Photo courtesy of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

“It is gratifying, when you’ll be on the street and see somebody, and they say, 'I used the bookmobile. I want you to meet my four children. I insist that they read'.” -Allegra Westbrooks

Ms. Westbrooks influenced countless people in the Black community to go to libraries through her public service. People remember her visiting them with a bookmobile to inspire them to read. She would also pick up books that her patrons requested at Main Library once a week.

Brevard Street Library, c1947

The bookmobile resulted in increased circulation of Brevard Street Library materials, with November 1948 monthly statistics totaling 3,445, and November 1949 monthly statistics totaling 4,180. The 2,500 square foot branch proved too tiny for the frequent patrons, so Ms. Westbrooks recalls “the crowded conditions in the library make it necessary to ask persons to check out books and move on so that others may enter.” [19]

Charlotte’s public library system officially integrated in November 1956, but the Brevard Street Branch continued to operate until December of 1961 when it was closed and demolished as part of the Brooklyn urban redevelopment project. [20]

Back to Square One, 1966-2021

One librarian who operated a bookmobile throughout the 1950s described the work as “glorified missionary work,” and that she “couldn’t do better business or have a greater following if she had an ice cream wagon.” [21] The overwhelming popularity of the bookmobiles made the retirement of the two bookmobiles in 1966 extra disappointing.

The decision was not easy to make, but due to the growing expenses to operate the vehicles, the Library had little choice in the matter.

Looking “Foreword,” 2021 and beyond

Mobile Library, 2021. Photo courtesy of Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

Charlotte Mecklenburg Library places great importance on improving lives and building a stronger community. Director Caitlin Moen described the mobile library service in an official statement: “The new Mobile Library expands and deepens the Library’s ability to reach into high need areas of the community, providing access to free resources, programs and technology, particularly where limited physical or digital access to Library services exist. This access will help create pathways for citizens to learn and grow, gaining success in school, in their careers, and beyond.”

Collage of the new Mobile Library, 2021. Photo courtesy of Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

Our new bookmobile offers the following features:

- Shelving for a sizeable collection.

- An entrance and exit for easy customer flow through the vehicle

- An ADA compatible wheelchair lift

- Four mobile collection carts for pop up collections and displays

- A mobile technology cart to be equipped with laptops, Chromebooks, tablets and other technology.

- An air filtration system to help mitigate COVID-19 and other pathogens

- An onboard and external A/V system equipped with an external 65-inch display, and two additional displays inside.

- A speaker system with microphones for programming both inside and outside the vehicle.

- A diesel generator and a power inverter supported by four solar panels on the roof of the vehicle. This means our vehicle comes with lots of power and plugs for extra flexibility!

- 360-degree backup and side cameras to ensure safe parking and navigation.

The Mobile Library of today strives to provide equitable access to the underserved and underrepresented communities of Mecklenburg County. In the words of William Shakespeare, “What’s past is prologue.” And so, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library’s bookmobile journey continues!

--- This blog was written by Sydney Carroll, Archivist of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room.

Footnotes

[1] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), January 17, 1937: 63. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F7AC23928DF%402428551-15E3EBB49AF23875%4062-15E3EBB49AF23875%40.

[2] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), December 2, 1937: 3. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F7E8E938003%402428870-15E3EBB57AE3E5BB%402-15E3EBB57AE3E5BB%40.

[3] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), July 28, 1937: 10. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F82B2F74FAF%402428743-15E3EBC385AB9ACC%409-15E3EBC385AB9ACC%40.

[4] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), March 27, 1938: 23. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F7FF075EB0B%402428985-15E3EBBDE645BB68%4022-15E3EBBDE645BB68%40.

[5] Ryckman, Patricia. “Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County: A Century of Service.” Charlotte, N.C.: Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, 1989.

[6] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), February 10, 1942: 6. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F969D1C3A7C%402430401-15E3EBDA369620FA%405-15E3EBDA369620FA%40.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), November 20, 1941: 12. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F9595CCECED%402430319-15E3EBE530C592C3%4011-15E3EBE530C592C3%40.

[9] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), November 30, 1941: 15. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F9596838AD7%402430329-15E3EBE548945201%4014-15E3EBE548945201%40.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), October 16, 1942: 30. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F99CDD33BB5%402430649-15E3EBE6CF4E4B32%4029-15E3EBE6CF4E4B32%40.

[12] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), January 21, 1943: 11. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E3F0BF73D3C837%402430746-15E3EBDBA7D7A791%4010-15E3EBDBA7D7A791%40.

[13] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), April 20, 1945: 21. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E3F0D08E6DF4A7%402431566-1604902CAFDF846A%4020-1604902CAFDF846A%40.

[14] Ryckman, Patricia. “Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County: A Century of Service.”

[15] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), October 19, 1948: 12. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24FAC7192B6AB%402432844-1604904181FE53BF%4011-1604904181FE53BF%40.

[16] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), December 23, 1949: 16. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F9B8A73B044%402433274-1604905606B5F952%4015-1604905606B5F952%40.

[17] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), April 28, 1949: 20. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24FA9547A0DE3%402433035-1604904B5256A446%4019-1604904B5256A446%40.

[18] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), March 9, 1949: 15. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24FA8F7A9DD01%402432985-16049049D4EA84A9%4014-16049049D4EA84A9%40.

[19] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), December 23, 1949

[20] Ryckman, Patricia. “Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County: A Century of Service.”

[21] Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), June 17, 1960: 39. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F22B5DE010C%402437103-15E249FF0AF35320%4038-15E249FF0AF35320%40.

Bibliography

Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), February 4, 1939: 6. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15F6614CD140FE6A%402429299-15F6012A55D03F72%405-15F6012A55D03F72%40.

Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), September 17, 1941: 13. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24F94E4E49118%402430255-15E3EBE18E7A4886%4012-15E3EBE18E7A4886%40.

Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), July 29, 1948: 27. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E3F0DFC7166689%402432762-1604903ACEB0627A%4026-1604903ACEB0627A%40.

Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), March 9, 1949: 28. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24FA8F7A9DD01%402432985-16049049D591D32B%4027-16049049D591D32B%40.

Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), March 24, 1949: 18. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A11260DC9BB798E30%40EANX-NB-15E24FA8F8C6A1B5%402433000-16049049F23A80AA%4017-16049049F23A80AA%40.

For the second year, the Library has been honored to partner with Carowinds. Not only does Carowinds generously donate tickets to encourage our community to read and learn all summer long, but they celebrate literacy during Library Week – where library cardholders receive discounted tickets and enjoy storytimes at the theme park. Thank you, Carowinds!

For the second year, the Library has been honored to partner with Carowinds. Not only does Carowinds generously donate tickets to encourage our community to read and learn all summer long, but they celebrate literacy during Library Week – where library cardholders receive discounted tickets and enjoy storytimes at the theme park. Thank you, Carowinds! An important partner in all Library ventures is the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library Foundation. Their support this year has been crucial in facilitating programs reaching all populations – from infant storytimes and programs for people with special needs to outreach to the elderly. Thank you, Library Foundation, for contributing to the ongoing success of Summer Break!

An important partner in all Library ventures is the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library Foundation. Their support this year has been crucial in facilitating programs reaching all populations – from infant storytimes and programs for people with special needs to outreach to the elderly. Thank you, Library Foundation, for contributing to the ongoing success of Summer Break!

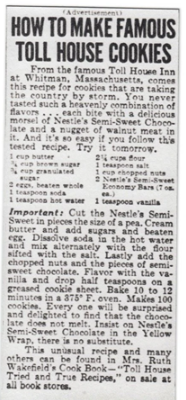

Chocolate Chip Cookies (originally known as “Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookies”) were invented by Ruth Wakefield circa 1938. Aside from being recognized as the creator of this delicious treat, Wakefield is also known for running the Toll House Restaurant in Whitman, Massachusetts from 1938-1967 with her husband, Kenneth.

Chocolate Chip Cookies (originally known as “Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookies”) were invented by Ruth Wakefield circa 1938. Aside from being recognized as the creator of this delicious treat, Wakefield is also known for running the Toll House Restaurant in Whitman, Massachusetts from 1938-1967 with her husband, Kenneth.

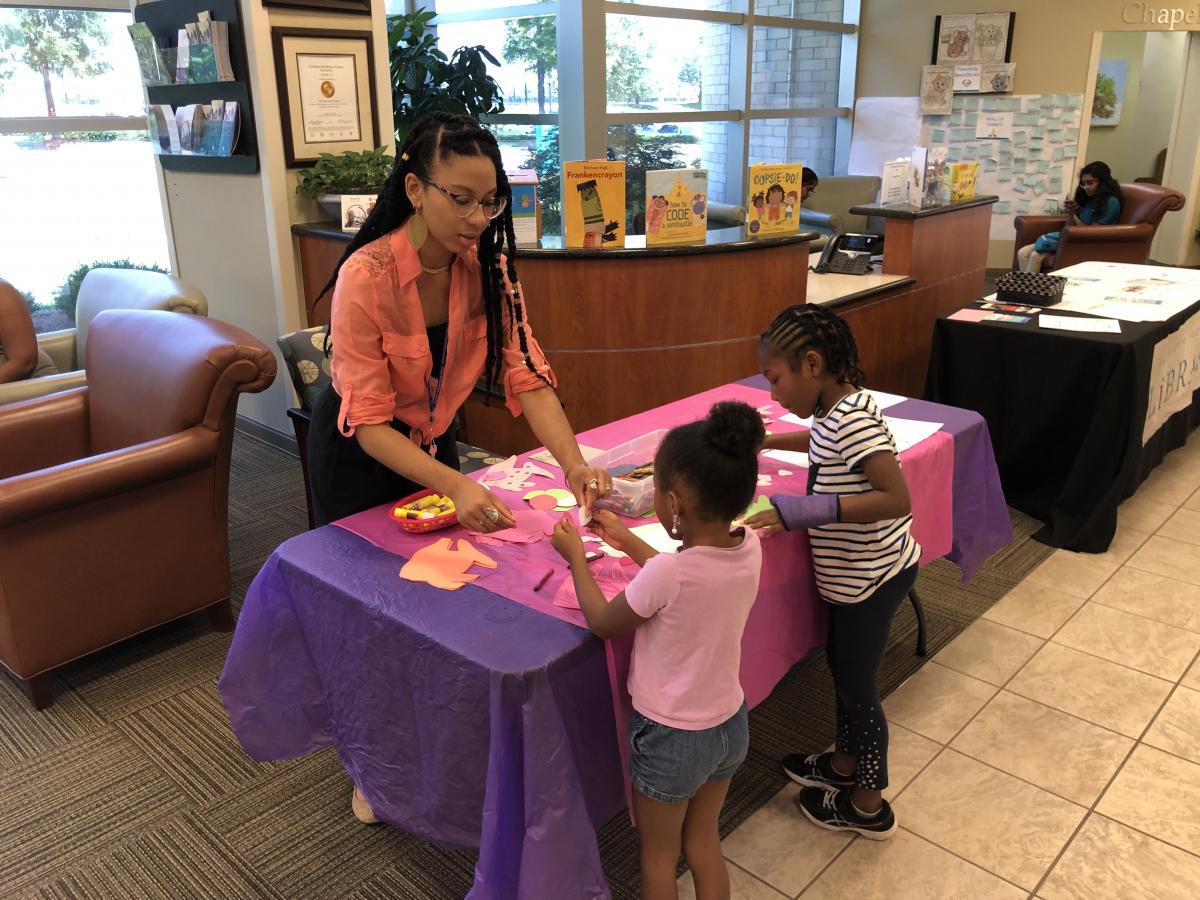

“This compulsory school education seems to be failing a large percentage of these children. It’s not coming through on its promise to educate. We’re at the library showing we can create a learning environment in which children can have a good feeling about reading, and we found that they responded in a remarkable way.” - Dennis Martin, Public Librarian

“This compulsory school education seems to be failing a large percentage of these children. It’s not coming through on its promise to educate. We’re at the library showing we can create a learning environment in which children can have a good feeling about reading, and we found that they responded in a remarkable way.” - Dennis Martin, Public Librarian

Why buy books where you can borrow them for free? Library staff member Helaine Kranz explains: “People are looking for something special. Some are teachers or parents, building a classroom or home library. Others are collectors, looking for an unexpected treasure. One customer found a vinyl record she’d been searching for, another purchased a signed copy of Jimmy Carter’s autobiography. It’s the Library version of Pawn Stars – you never know what you’ll find!”

Why buy books where you can borrow them for free? Library staff member Helaine Kranz explains: “People are looking for something special. Some are teachers or parents, building a classroom or home library. Others are collectors, looking for an unexpected treasure. One customer found a vinyl record she’d been searching for, another purchased a signed copy of Jimmy Carter’s autobiography. It’s the Library version of Pawn Stars – you never know what you’ll find!”

Swing by the Children’s Area to dance on the cool underwater area rug or read a book in our treehouse. University City has a lot of children’s materials including more than fourteen shelves of graphic novels, educational computers, board books for babies and rentable tablets preloaded with educational apps. Teens can hang out and relax in the Teen Zone while adults browse the large print collection or magazines. University City Regional Library has a diverse collection of books in international languages including Spanish, Arabic, Russian, Chinese, Gujarati, French, Korean and other languages. We really have something for everyone!

Swing by the Children’s Area to dance on the cool underwater area rug or read a book in our treehouse. University City has a lot of children’s materials including more than fourteen shelves of graphic novels, educational computers, board books for babies and rentable tablets preloaded with educational apps. Teens can hang out and relax in the Teen Zone while adults browse the large print collection or magazines. University City Regional Library has a diverse collection of books in international languages including Spanish, Arabic, Russian, Chinese, Gujarati, French, Korean and other languages. We really have something for everyone! After visiting University City Library, check out the

After visiting University City Library, check out the